By Vivek Menon

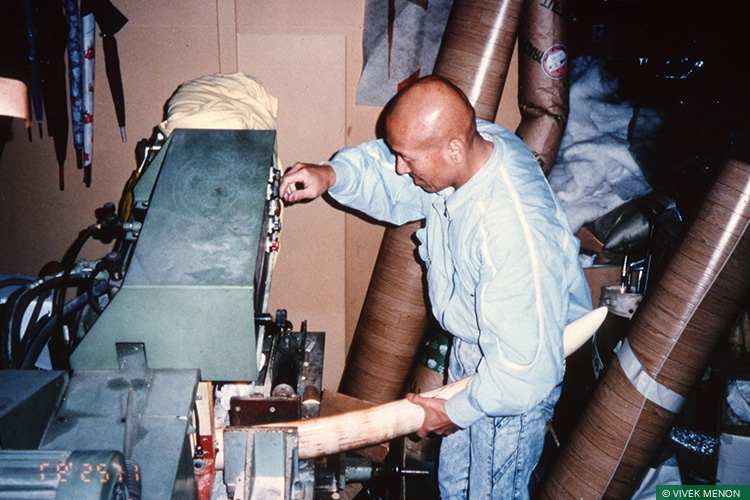

An ivory-processing unit in Japan that the author came across during a wildlife crime control operation in 1997

An ivory-processing unit in Japan that the author came across during a wildlife crime control operation in 1997

“Yuck! Dad! Is this not the weirdest thing you have ever seen?” my son walked in brandishing a copy of Sanctuary in front of my nose.

The article on the internet trade of monitor lizard penises being busted by the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau assisted by the Wildlife Trust of India was nothing new to me. The photo he was pointing to, of a shrivelled organ looking somewhat like a pair of hands folded in prayer, was weird indeed. But I felt no amazement. And it was certainly not the weirdest thing I had ever seen.

Five Hard Lessons

Twenty-five years ago I had spent a substantial portion of my daylight, and part of my nights as well, tracking wildlife crime. Mentored by the trailblazing Ashok Kumar I had gone undercover into Gali No. 11 in Delhi’s Sadar Bazar, the headquarters of the tiger bone trade at that time. I had spent months surveying the barter of guns for wildlife and women for drugs on the Myanmar border, digging up info on the rhino horn trade. I had dealt with the Yakuza in Japan, traded fisticuffs with elephant poachers in the south of India and learnt how to set snares for clouded leopards in the north-east. In the Philippines I had travelled to forbidden Mindanao to deal with ivory traders and in the process caught a deadly pneumonia; in Taiwan I had raided the night markets where wildlife was traded; and in Macao I had gambled in a five-star casino where most ivory ended up being traded. All this was long ago and now ensconced in a comfortable armchair, worrying about the workings of one of India’s larger not-for-profit organisations dealing with nature conservation, I could afford to dial up memories of the past and say: “Not surprised!”

Not to say that I had seen them before, these dried reptilian jewels being touted as a panacea to the gullible. But not to be surprised by anything new was one of five major lessons taught to me in the business of unravelling wildlife crime. Come to think of it there are small stories behind all of them, so here goes.

Lesson No. 1: Never be cocksure about what is traded in the underworld of wildlife crime. And when you learn of it, never be surprised.

In the early 90s the legendary American wildlife guru George Schaller wrote in to Ashok and me about hundreds of Tibetan antelope being massacred on the Tibetan plateau. Their wool, he told us, was being smuggled into India. “What would we do with the wool of an antelope?” we conferred. Nada. It could not be. We wrote back, foolishly, asking whether he was sure that the wool was coming into India, for there could be no earthly use for antelope wool in India. We know now that this was shahtoosh, used by Kashmiri weavers to craft the world’s most expensive shawls, but those were the days when people believed that shahtoosh was the wool of some high altitude goat. Lesson No. 1: Never be cocksure about what is traded in the underworld of wildlife crime. And when you learn of it, never be surprised.

Cut to a few years later. Undercover in a stifling basement in Yashwant Place market, Delhi, with a Spanish WWF colleague who was using his Hispanic descent and passport to open doors that were usually closed to Indians. He was the tourist looking to buy an expensive fur coat for his girlfriend, I was the tour guide. Deep in the bowels of the market the goods were unwrapped. A snow leopard coat: 15,000 dollars, the quoted price. The undercover agent had to seal the deal now. But he was hot and bothered. Without a thought he took off his black faux-leather jacket, revealing in all its telltale glory a white WWF T-shirt with a snow leopard and the words ‘Save Snow Leopards’ emblazoned on it. I am unsure how we managed to get out of that basement but we learned Lesson No. 2: Concentrate on the small details. For in the world of busting crime, you rarely get second chances.

The author with an elephant tusk, part of a larger cache of ivory seized during an operation conducted in September 2002

The author with an elephant tusk, part of a larger cache of ivory seized during an operation conducted in September 2002

The third lesson was learned deep in the southern jungles ‘buying’ ivory from a poacher and his middlemen. After vouchsafing that the ivory was genuine, the signal for the back-up team to arrive was given. There were four criminals in the dark shack and I was the only one with them. The three others in my team were in a jeep supposedly counting the money for the ivory and only one was armed. Suddenly the sound of a jeep approaching could be heard. My back-up, surely. I led the poachers out to receive their payment. The jeep arrived on cue but it wasn’t the required armed support – it was a media crew brandishing a video camera. He had overtaken the enforcement team to get his shot head-on. “What the hell is going on?” I shouted before I could be asked the same question by the poachers, swinging at the nearest man. The drama caught them by surprise for just enough time for the real back-up vehicle to arrive. But it was a close shave. Lesson No. 3: Keep the media well away when doing undercover work. It is just not worth it in the final analysis.

Lesson four was learned in multiple exposures. On the Burmese border looking out for a key rhino horn buyer, I sat watching a group of tough looking men drink and brawl and bicker over their women. Which one could it be, I wondered? The toughest looking one, or the one with all the money, or the other one dealing cards insouciantly, with an air of inherited intelligence that the other two clearly didn’t possess? I waited and watched for two weeks while a peanut vendor crossed the border daily with his push cart and possibly a cargo of rhino horn. Lesson No. 4: Never go by appearances. No one in this business looks like their real self. Even I, after all, was not who I was taken to be.

Lesson No. 4: Never go by appearances. No one in this business looks like their real self.

Finally, Lesson No. 5: Never put down money. Something I learnt not from personal experience but from the tales of others. It is a great temptation to leave an amount for promised wildlife deliveries, but ever so often the money is used to procure goods that were till then still alive. Two instances, once of a leopard and another time of musk deer killed for people who put down money in their haste to get a seizure, come to mind. Ashok was crystal clear in that teaching. All the show money carried by us was a layer of notes covering Hindustan Times clippings in a brown duffel bag.

There are more lessons and many, many more stories. But for that I must write a film script. This we must end here, with the added note that the weirdest thing I have ever seen is a live monkey scalped and with its skull cut away, for a cancer patient to dip into the bloody cranium and eat its brains. Wildlife crime is a cruel, wanton waste of life and the fight against it is a moral, legal and ecological necessity of our times.

The author is Executive Director, Wildlife Trust of India and Senior Advisor to the President, IFAW. THis article was originally published in the October 2017 issue of Sanctuary Asia.